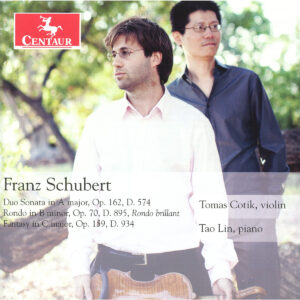

Schubert’s music for violin and piano

Schubert played both violin and piano. His father taught him the basics of the violin, and his brother Ignaz gave him piano lessons. At the age of seven, Schubert began receiving lessons from Michael Holzer, the local church organist and choirmaster. Josef von Spaun, a law student and friend of Schubert’s at the Stadtkonvikt, wrote: “Schubert, scarcely twelve years old, played second violin in the students orchestra. His extraordinary interest in the masterworks performed, however, soon drew the attention of those around him to his superior talent and the little boy was soon installed as leader at the head of the orchestra.” In his initial grade reports from the Imperial and Royal Seminary he received the highest mark for violin. During that time Schubert also attended choir practice with his fellow pupils and played the organ. He also played the viola in his family’s string quartet with his father on cello and his brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand on violin. Ferdinand, who played first violin, wrote: “…it was an uncommon pleasure to play quartets with him… The youngest of them all was the most sensitive there.”

Read More

Some notes on our interpretation

Our primary goal in approaching these pieces was to make informed decisions and interpretations inspired by knowledge of Schubert’s times. To this end we researched the historical context of each piece in order to know what the usual practices in interpretation were at the time of its composition. At the same time, we recorded with modern instruments and tried to incorporate our own modern esthetical understanding of the pieces into the historical frame.

Another goal was to preserve the creativity and spontaneity of live performances by capturing the natural sound of the concert hall and doing takes from whole movements or pieces during the recording. What follows is a synthetic description of certain aspects of our research and interpretive decisions.

For a violinist, one of the ways to approach the style and tonal qualities of original instruments is not to apply too much pressure with the bow. Pianists using modern instruments can approximate some of the characteristics of a pianoforte of Schubert’s time by avoiding emphasis on strong dynamics in the outer registers and thereby emulating the weaker outer register of the 5 ½ to 6 octave pianoforte.<br><br>Another issue regarding sound is the use of pedals. In Schubert’s time, the pedals were used not as a standard resource for achieving legato passages or for facilitating technical execution, but rather for subtle special effects.

Regarding the use of vibrato on the violin, we know from the treatises about interpretation that some kind of vibrato—with variations, less uniform, and probably not on every single note—was used during Schubert’s time. It is very possible that it was used as an ornamental device and not as a standard continuous addition to the sound. <br><br>It is more difficult to be certain about the meaning of Schubert’s tempi. While Schubert did not put metronome markings on any of his instrumental works, some conclusions can be drawn from the contemporary metronome markings in some of his Lieder and in the opera “Alfonso und Estrella.” There are signs indicating that many allegro movements, according to Schubert’s choice and the practice of that time in Vienna, were performed faster than what is common in today’s performances.

We understand that Schubert wrote sufficiently expressive devices for his own purposes and doesn’t need the “assistance” of too much rubato from the performer. The baritone Johann Michael Vogl (1768-1840, who was not only Schubert’s close friend but the singer whom Schubert admired above all others, nevertheless recounts that during rehearsals, Schubert would frequently admonish him with: ‘Kein Ritardando’ or ‘Keine Fermate’ (‘No ritardando,’or ‘No fermata’). Schubert seems also to have desired very smooth, seamless transitions at meter changes. In a letter dated May 10, 1828, to the publisher Probst regarding the E-flat Piano Trio, D. 929, he has this to say: ‘See to it that really capable players are found for the first performance, and above all, where the time changes in the last section, that the rhythm is not lost.’ …

Read More